Twab Controller

What is it?

The Time-Weighted Average Balance (TWAB) Controller is a system that keeps track of users token balances, their historic balances and their average balances of historic time periods. It is calculated by looking at the balances held during a queried time period, weighting them based on the duration they were held and returning an average amount held for the whole time period.

This ability to look back in time is critically important for PoolTogether, so that users can deposit and withdraw freely into a prize pool while having their liquidity contribution measured perfectly.

For example:

- If a user held 100 tokens for 1 week, then their average balance over that time was 100.

- If instead they held 100 for half of the week and then 200 for the second half, then their average for the week would be 150.

How Does it Work?

We record a special data structure called an “Observation” on each transfer which includes the information needed to look back in time and see how many tokens a user held at a specific point in time. This allows us to calculate a simple average over two points in history.

Observations

When a token transfer occurs we record an Observation. An Observation is a chunk of data that consists of: the time the Observation happened, the users current balance (the balance AFTER the transfer) and a “cumulative balance”. This record of data is what is used to look back in time and see past balances held.

We store a enough observations to allow historical lookups for up to 1 year. After that point, old data may be overwritten for new data to save gas costs.

New Observations

Every time an Observation is recorded we do a small calculation to get the new data to save.

- The balance to record will be the current balance (the balance AFTER the transfer).

- The timestamp will be the time that the recording of the Observation is happening.

- Finally the cumulative balance, which is where the bulk of the information is. The new amount is calculated taking the previous cumulative balance and increasing it with the previous balance (the balance BEFORE the transfer) multiplied by the time that it was held for (current time - newest Observation time). This multiplication is the “time-weighted” bit and it ensures we retain information about how long each balance was held for. This number is always increasing and is heavily inspired by Uniswap’s TWAP.

Recording an Observation

Not every transfer results in a new Observation. Sometimes when we record an Observation we instead overwrite an old Observation with new data. The new data is always computed as described above but if the time that the Observation is being recorded falls within the same “period” compared to the most recent Observation that we have saved we overwrite it rather than logging a new one.

It is imperative that PoolTogether uses periods that are smaller than a single draw. By overwriting historic Observations we enable significant gas reductions at the cost of losing granular timestamp data within a period. If a draw were to start and end within a period a user would be able to alter the record of their balance for that draw by overwriting an Observation.

Periods

A period is simply a block of time in which we should overwrite Observations. When a new period begins, a new Observation should be created. Periods are calculated by taking a timestamp, subtracting a reference timestamp that represents the start of the first period and dividing it by the period length being used.

Periods work best for PoolTogether when lined up with draws. This is done by simply recording a timestamp on initialization by reading the last completed draw and by using a period length that is some fraction of a draw length.

It is not necessary to do this, however it is important to note that due to Observation overwriting, average balances for a period are not finalized until a period ends. Therefore if a draw ends but a period has not, a user would be able to manipulate their average balance for that final period of time after the draw ends. This would result in an inaccurate record of their balance held during the draw. Twab periods are therefore aligned with prize pool draws to ensure accurate accounting for the duration of a draw.

Calculating a TWAB

To calculate a time-weighted average balance over a period of time we need to:

- Look in our record of Observations for the closest records BEFORE OR AT each timestamp in our requested time range to get the newest Observation BEFORE OR AT the start time and the newest Observation BEFORE OR AT the end time.

- If the Observations we found were recorded exactly at the start time and end time then we can use them in the next step. However, they likely don’t match exactly and we will need to calculate temporary Observations for the next step.

- To calculate a temporary Observation for a specific time we use the newest Observation recorded BEFORE the time we want. Using the balance stored in the Observation and the difference in time between the time the Observation was recorded and the specific time we want we can compute exactly what the cumulative balance would be at that time. With the time requested, the new cumulative balance and previous balance we have a new Observation that we can use.

- Using the Observations for each end of the time range the rest is just a standard average calculation: the change in cumulative balances between the two Observations divided by the change in time between the two!

Sample Sequence of Events

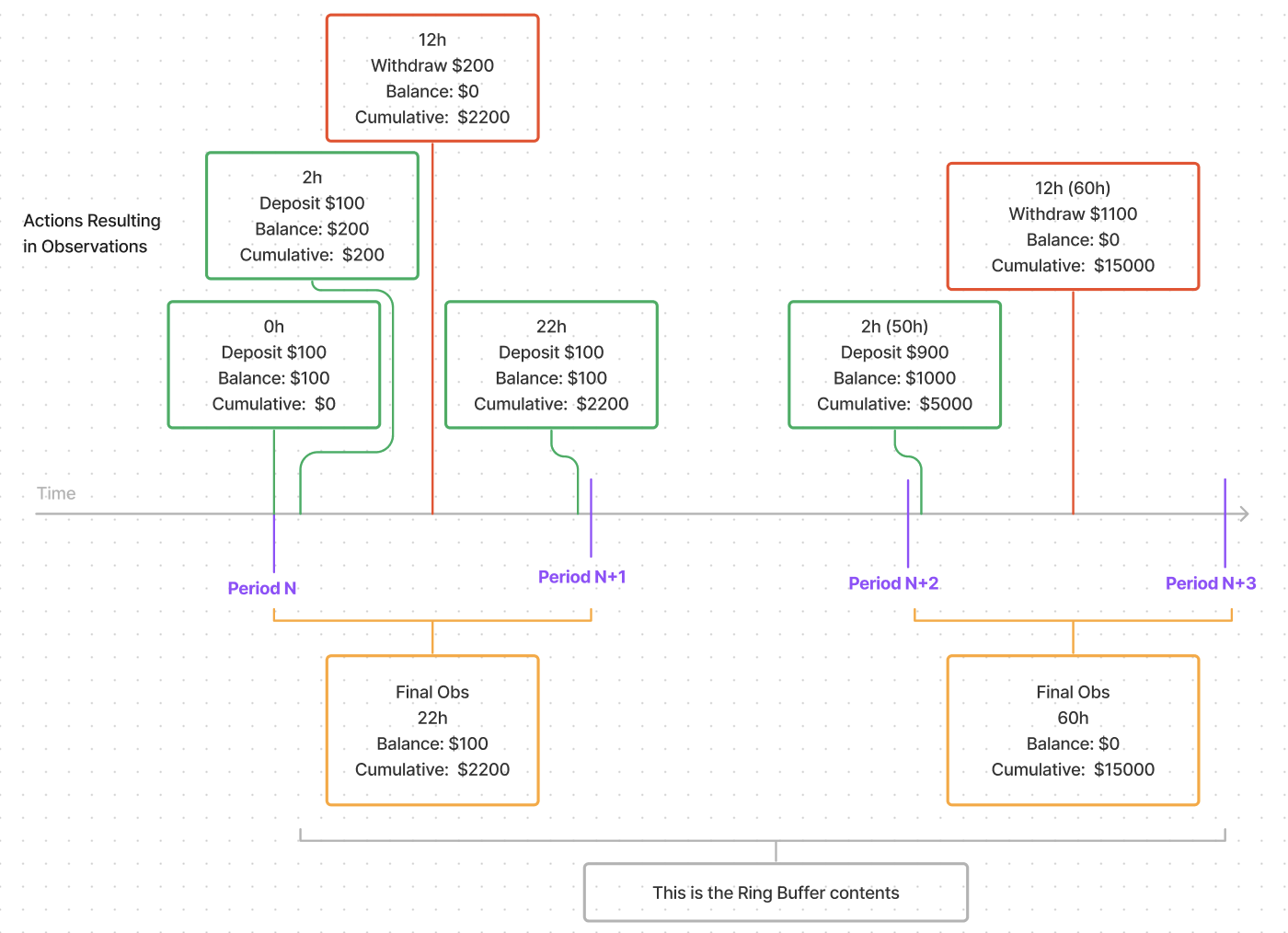

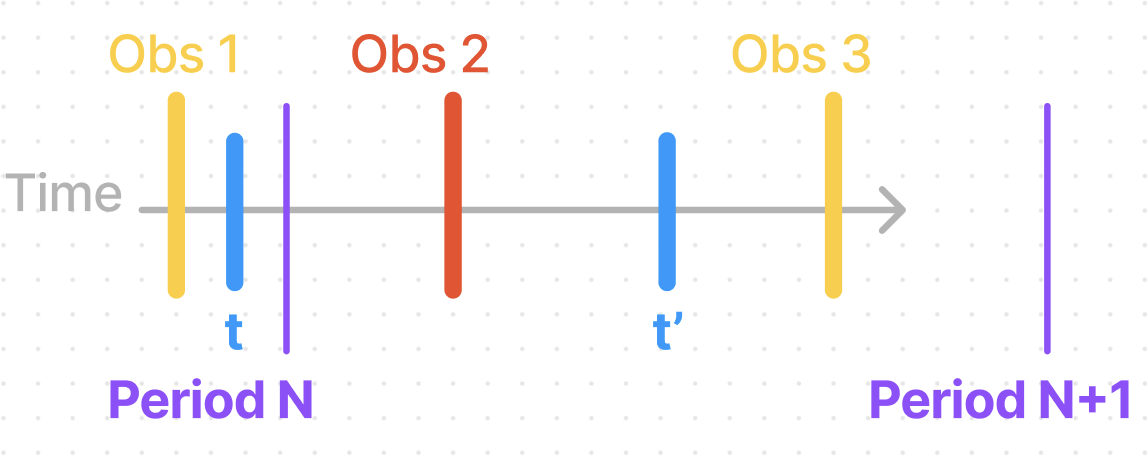

Time flows from left to right. You can see here the transfers that cause Observations to be recorded, the final Observations that we would have stored, and some calculations to show the recreation of historic balances.

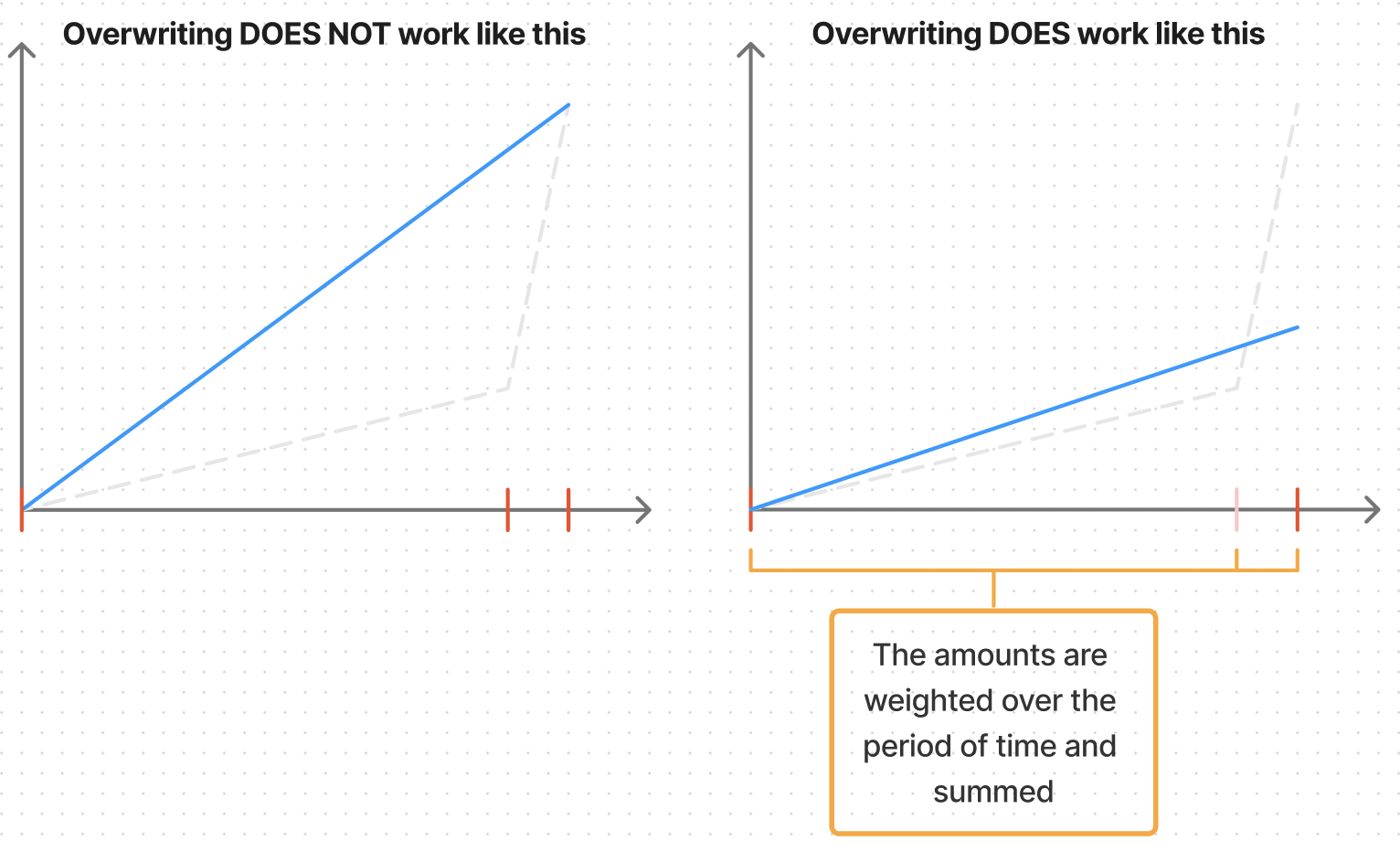

Observation Cumulative Balance Overwriting

At a first glance, overwriting Observations may seem like we’re losing information. But since we are calculating the cumulative balance by weighing the balances by the amount of time the result is as follows.

Limitations

Data Limits

To optimize this data structure for gas savings we are tightly packing it all into a small footprint. The result of this is some limitations on the maximum values for each piece of data. Assuming the token in use has 18 decimals of precision, the limits are as follows:

Balance: 79,228,162,514 (79.2 billion)

Meaning no user may hold a balance greater than 79.2 billion. To handle tokens with very large supplies they must be wrapped into a high-denomination token.

Cumulative balance: 340,282,366,920,938,463,463 → ~10,783,118,943,836/s for a year (10.7 trillion per second for a year)

Meaning no user may hold more than 10.7 trillion tokens per second for a year on average. This limit is near impossible to reach due to the limitation on the balance.

Timestamp: 4,294,967,295 / 31,556,952 s → 136.1020955066 years

Meaning we are able to track this information for the next 136.1 years. We’ll need to find a new solution before that time comes.

Historic Balances Accuracy

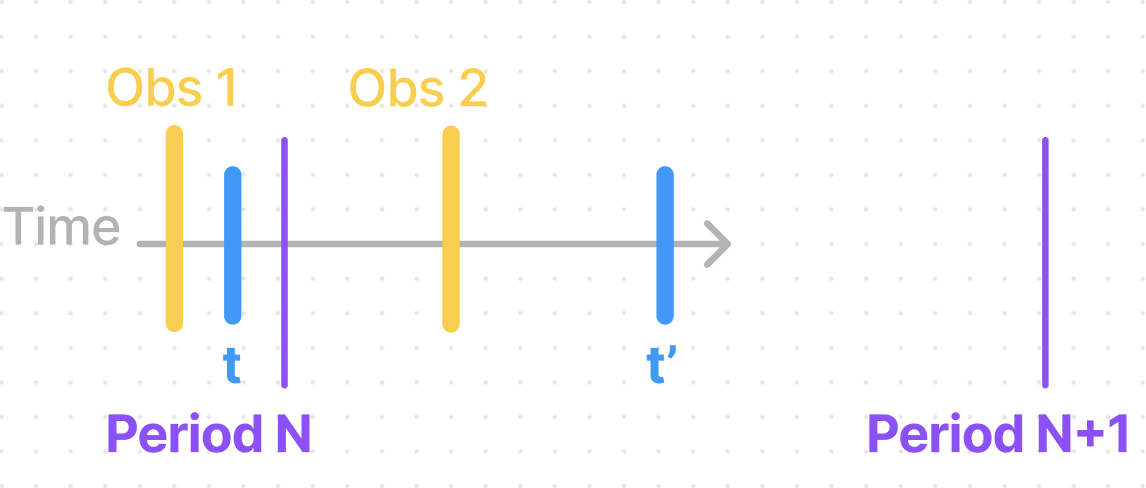

Historic balances are only guaranteed to be accurate when querying for a time *t* that falls between (inclusive) the newest Observation recorded before the end of period N and the end time of period N where period N is a period that has ended. Due to overwriting Observations for the sake of saving gas, there is a loss of historic information and no guarantees on information until the period has finished.

Any time t’ that falls between (exclusive) the start of period N and the newest Observation before the end of period N (assuming there is an Observation that falls within period N) may have previously had an Observation that has since been overwritten. Therefore we may be missing data to accurately recreate a temporary Observation for time t’.

If we can verify that there has been no overwriting of Observations during the time that t’ falls within then we can accurately recreate the temporary Observation for time t’.

Historic Average Balances Accuracy

The results noted above extend to querying average balances across time ranges as well. Historic average balances from time s until time t are only guaranteed to be accurate if both s and t fall between (inclusive) the newest Observation recorded before the end of the period and the end of the period for the periods that s and t fall within where the periods that s and t fall within have ended. Due to overwriting Observations for the sake of saving gas, there is a loss of historic information and no guarantees on information until the period has finished.

Any other time t’ may be missing data due to overwriting therefore we cannot guarantee the accuracy without additional validations of our data set.

Periods aren’t finalized until they’re finalized

It sounds obvious but a period is not finalized until the full period length has passed by. It is important to keep in mind that a historic balance or an average balance for a time range is not finalized until the periods that are being queried have ended. If the period has not ended then a user can still take actions that result in Observations that will result in overwrites that will ultimately alter the resulting average balance for that period.

If time *t* falls within period N and period N has not finished at the time of querying then the resulting historic balance at time *t* may potentially change.

This extends to average balances queried across time range s to t as well. If either time *s* or *t* fall within a period that has not ended then the average balance for that time range may potentially change.

Loss of Historic Information (Overwriting Observations)

As noted above, when overwriting Observations we are trading some information for gas savings. The data that is lost is the specific timestamps at which balances were held throughout the period. The result of this compression of information is that we cannot accurately query for a balance for every historic timestamp however we can guarantee that queries for balances for some timestamps will be accurate.

The newest Observation before the end timestamp of a finalized period N is guaranteed to be an accurate snapshot of history since we know it will never be overwritten. The data included in this Observation allows us to accurately reproduce a temporary Observation at any time between (inclusive) this Observation and the end time of period N.

When we are calculating average balances across time ranges if we are able to accurately recreate temporary Observations on both ends of the time range and have been capturing time-weighted balances throughout the time range then we are able to accurately reproduce the average time-weighted balance held across that time period.

Sample Loss of Historic Information

Since there have been no changes between Observation 1 and the start of Period N we can guarantee that the temporary Observation created at the start of Period N is an accurate log of their historic balance.

- When querying the balance at t the balance will be X, some number calculated using Observation 1.

- When querying the balance at t’ the balance will be X’, some number calculated using Observation 2.

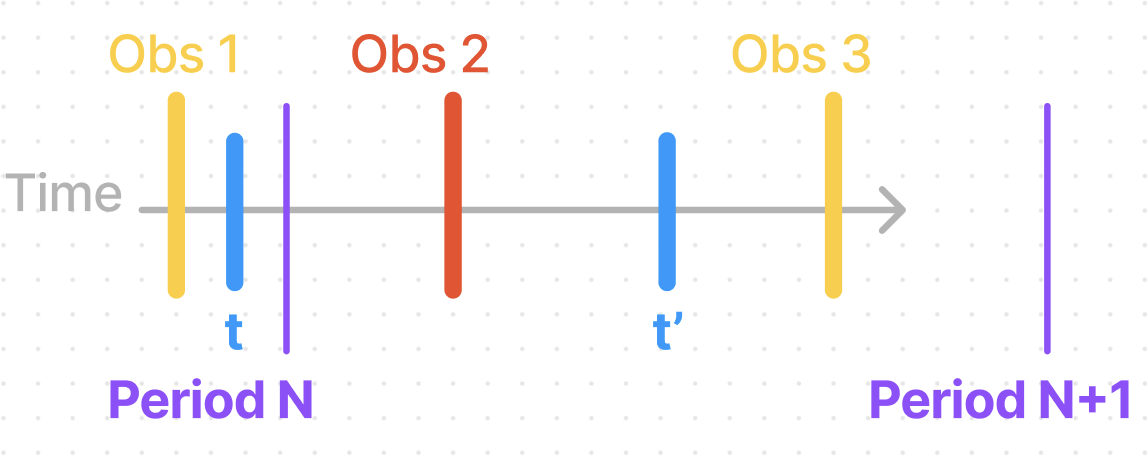

As time progresses, the user takes some action after time t’ that results in Observation 2 being overwritten with Observation 3.

- When querying the balance at t the balance will still be X, some number calculated using Observation 1. Since period N-1 has ended and time t falls between the newest Observation before the end of period N-1 and the end of period N-1, the balance will stay consistent and will be an accurate balance at time t.

- However, when querying the balance at t’ the balance will be Y’, some new number calculated using Observation 1, resulting in an inaccurate balance at time t’. Before Observation 3 was created a temporary Observation created at time t’ would have been an accurate representation of history, since it was a time between the newest observation & the period ending. However, period N had not finished, so there was no guarantee that this would persist. After Observation 3 was created the queried balance for time t’ is no longer guaranteed to be accurate.

This example scenario shows both that periods aren’t finalized until the full duration of the period has elapsed and highlights the impact of the loss of information when overwriting Observations.

Historic Average Balance Manipulation (Overwriting Observations)

This loss of information can be used to someones advantage if the Observations are not being used properly. As we’ve seen above, by overwriting an Observation a user can alter historic data, resulting in an inaccurate result from a balance query. If a user knows that someone is querying balances at wrong timestamps and relying on this data then with a few well crafted Observations a user would be able to manipulate their historic balance.

Assume a PoolTogether draw spanned from time t until time t’. If a user held 10 tokens at Observation 1 and 0 tokens at Observation 2 then we can simply compute that their average balance over the duration of the draw the result was 5 tokens (10 for half, 0 for the other half). However, after the creation of Observation 3 we’ve lost the exact time that their balance went to 0. This means that querying their balance for the time range t to t’ would result in an average balance of 10 tokens for the duration of the draw which is incorrect.

This scenario stresses the importance of querying at times that are guaranteed to be accurate representations of history for important procedures.